Warehouses: Unsung heroes of the modern world

Opinions expressed whether in general or in both on the performance of individual investments and in a wider economic context represent the views of the contributor at the time of preparation.

Executive summary: There is much more to warehouses than meets the eye. They are critical to the functioning of the global economy. From an investment perspective, the industry can be considered highly attractive, growing faster than global GDP, with demand heading only one way and supply being constrained. Demographics and technology are accelerating consumption patterns while every business has had to think about increasing supply chain resilience since the pandemic. Limited numbers of new buildings are also driving warehouse innovation. Future warehouses are likely to be both greener and more automated. Investing in logistics real estate businesses, or companies that operate in close adjacencies, can be a compelling strategy owing to the consistency of their returns across cycles. While there is a scarcity of pure-play assets, Prologis (an owner-operator of real estate) and GXO Logistics (a major contract logistics provider) stand out as particularly strongly placed beneficiaries, in our view.

“The line between order and disorder lies in logistics” (Sun Tzu)

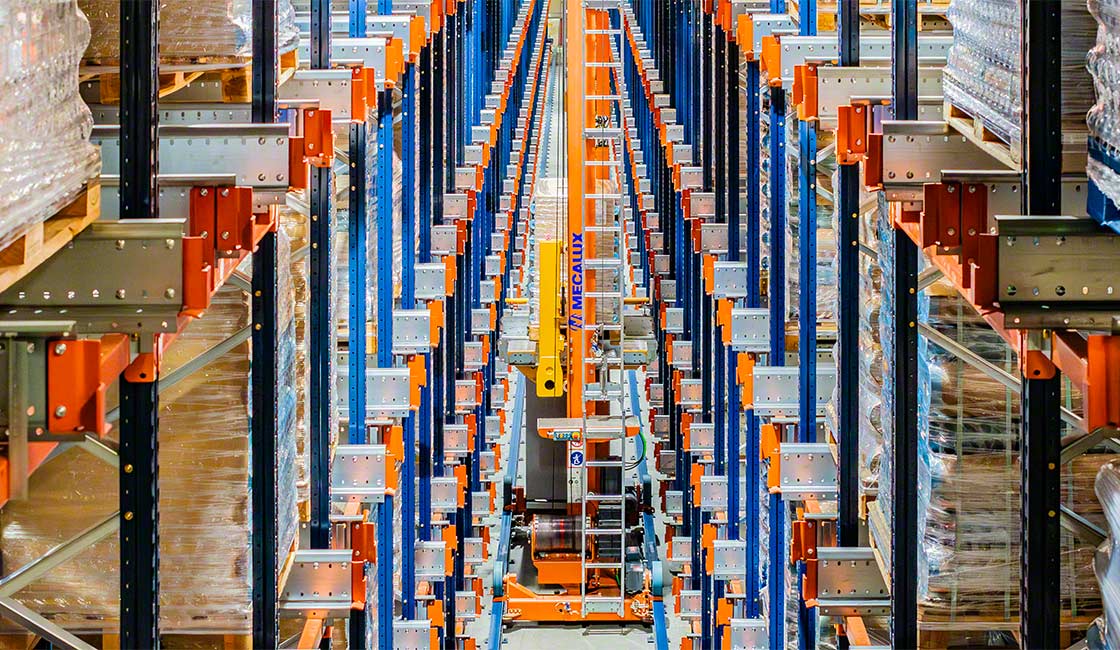

Few people normally get excited about warehouses. They are typically hulking grey edifices located in industrial parks on the outskirts of cities or at strategic locations such as motorway junctions. Even fewer have any reason to visit a warehouse. However, should the opportunity ever arise, your author cannot recommend a trip highly enough. Viewed from the inside, warehouses are absolute marvels.

The sheer scale of many warehouses is impressive. One, visited by your author in April, is of a size equivalent to 12 Wembley-sized football pitches. At peak it can hold up to 14 million units of stock and pick daily around 625,000 items. Another, visited in 2022, contains 750 metres of dedicated monorail track. Some of the trolleys on it travel 100km a day.

More importantly, consider that warehouses are essential to the global supply chain. They facilitate the flow of goods around the world. Memories of early COVID-19 lockdowns and shortages of everything from toilet roll to pasta should serve as a reminder of their criticality. The global warehousing and storage services market is valued at $300-600bn (depending on the methodology used) and is growing currently at a rate more than double GDP.

Think of warehouses, then, as must-have solutions for any company in the business of selling physical goods. Warehouses allow them to manage their supply chains and optimise their order fulfilment process. This, in turn, should result in increased productivity, more satisfied customers and higher profits.

So why are warehouses often overlooked? Put simply, for most businesses, rent is a fraction of total supply chain costs. Consultant CBRE estimates that transportation is the single largest cost in this respect (45-70% of the total burden) followed by variable facility costs including labour (15-25%) and then inventory costs (12-16%). In other words, while logistics typically comprises only 2-6% of overall supply chain costs, it can have a disproportionately large impact on consumer experience. As many readers will recognise, get the wrong items of clothing delivered or find something difficult to return and the likelihood of you using that company again is low.

No surprise then that logistics real estate is a growth industry. Demand is being driven by two main factors: consumption and supply chain resilience; or revenue generation and risk mitigation. Begin with consumption. It is the largest share of economic activity (c70% globally) and typically outperforms across economic cycles. Work from Prologis Research shows how retail sales have a higher correlation with logistics demand than do other factors such as manufacturing and trade.

Think of consumer demand as having three main sources: basic daily needs (driven by population growth), cyclical spending (or lifestyle upgrades) and structural trends (online shopping). These are split roughly equally, per estimates from Euromonitor. Against this background, demographics and technology are helping to change the face of retail. Not only does the Internet as a platform for commerce continue to expand around the world, but Millennials now comprise over 20% of the global population, according to the United Nations. This cohort, more than any other, has higher expectations, favouring convenience, choice, reliability and immediacy.

Even with regional variations, the global e-commerce market is growing at more than twice the rate of physical retail and will account for a 28% share of total global retail sales by 2027, per Activate Consulting. Crucially, online retailers use around three times more logistics space relative to physical retailers, according to Prologis, a major warehouse owner. This is a function of the much wider range of goods available online compared to in a physical store; or, as Jeff Bezos once described it, the marvel of “the infinite shelf.” In addition, the shift from pallets (sent to physical stores) to packages (delivered to homes) requires more space, as does the growing need for reverse logistics. A positive returns experience for unwanted items is critical to retaining customers. For retailers, the ability to reposition returned goods for resale also matters.

The second major driver for warehouse demand is the need for supply chain resilience, which has been exacerbated recently by geopolitical considerations. For decades, supply chains had been moving to globalise, take advantage of cost differentials and streamline to a just-in-time model to reduce inventory carry costs. However, disruptions to this model have extended beyond natural disasters, congestion, and labour disputes to include major trade renegotiations and a global pandemic. As a result, the industry paradigm has moved from just-in-time to just-in-case.

Prologis estimates that for every Dollar of US GDP, at least 20% more logistics space is needed than before the pandemic. This contention is supported by recent work conducted by McKinsey, which confirms that 78% of supply chain leaders say that they are now using inventory buffers and dual sourcing strategies, while 49% believe that disruptions have caused major planning challenges over the past year. Another study (by EY) highlights that over 50% of European companies it surveyed state that they are looking to create more regionally based supply models.

At the same time that demand is heading only in one direction for warehouses, new warehouse building supply is falling sharply, and will only become harder to deliver in the future. This creates an attractive potential investment opportunity, in our view. Since supply chains can be considered as a key source of competitive advantage, location matters more than ever for logistics and real estate customers. Proximity to customers is essential, particularly in the context of reducing transportation costs for suppliers (and recall, transport is by far a larger cost item). Further, a recent MIT study on carbon emissions reveals that adding an urban fulfilment centre can cut transportation emissions (and therefore costs) by half compared to out-of-town distribution.

The problem, however, is that the world’s urban population has doubled over the past 30 years and is forecast to double again over the next 30 years, according to the United Nations. Urbanisation drives competition to use land effectively, but it also increases demand for warehouses. Barriers to supply are therefore rising owing to zoning restrictions about where new properties can be built. Consider also the context that a 5-acre warehouse requires 10-12 acres of land owing to the logistics of transport coming both in and out. No surprise then that warehouse occupancy rates at Prologis (the source for the above statistic) are currently running at over 95%. This is a global average figure. In some regions, vacancy rates may be as low as 1%.

There is a strong argument, then, for retrofitting warehouses to make more efficient use of space. The average age of a warehouse building in the US is over 40 years. More than 82% were built before 2000 and some 30% of assets are more than 50 years old, according to CBRE. Put another way, the warehouse of the future will likely be taller, greener and more sustainable, whether retrofitted or built-to-suit from scratch. Expect solar panels on the roof, water recycling systems and EV charging points across the site.

However, as we noted at the outset of this piece, it’s what’s inside that matters as much as the location of the warehouse. Any innovation that can help with receiving, stocking, picking, packing and shipping should be under consideration. An automated warehouse facility can have a smaller footprint with the same throughput, potentially saving between 10% and 50% on square footage, according to research by Prologis. Meanwhile, work by GXO, a major contract logistics provider, suggests that cost per unit can be improved by between 50% and 80% via automation. Full warehouse automation, per GXO, can also reduce the number of employees needed by up to two-thirds.

There’s more to come too. Project forward and future warehouses could contain advanced automation solutions with intelligent robots capable of sorting, picking and packing. Many of these activities are currently complex owning to varying picks and packet sizes, providing a source of potential future upside. These intelligent machines could plausibly form part of a broader cloud-based system where routing activities are continually updated and optimised using a combination of machine learning and artificial intelligence. Last-mile delivery could also be enhanced via a combination of drones and self-driving robots. Both have a sustainability angle too. Think of a warehouse not just as four walls, but more as a service.

So, what might undermine the warehousing opportunity? We believe that the drivers outlined above are secular in nature. However, it is hard to deny the potential impact of cyclicality. For context, Prologis says that it sees goods with an economic value of ~$2.7 trillion flow through its distribution centres annually, representing ~2.8% of the world's GDP. Demand for goods is, of course, strongly correlated with trade patterns, consumer confidence and credit availability.

In addition, there is the challenge of finding new sites for warehouse conversion. Economic, political, physical and legal factors may constrain new builds. Many authorities prefer to use spare land for re-tenanting to housing. Zoning restrictions and tax considerations (warehouses typically raise fewer tax revenues than do rents from housing properties) are also potentially limiting factors. Assuming that warehouses do get built, there remain barriers to adopting automation. These also apply to owners of existing warehouse properties. Not only is there a fear of the unknown and a risk of disruption to business continuity, but some highly automated facilities may consume significant amounts of power, which will impact returns on investment.

Despite these concerns, warehousing demand should continue to grow faster than GDP, and the outsourcing of contract logistics at an even faster pace. As an asset class, logistics real estate has delivered consistent returns ahead of other comparable segments such as apartment, retail and office. From an investment perspective, there is a scarcity of pure-play listed assets. Beyond direct investments in physical property, which can provide a reliable source of passive income (from high rental yields, low maintenance costs, long-term leases and minimal tenant turnover), Prologis and GXO Logistics stand out as the two leading listed candidates to consider.

Founded in 1982, Prologis is the world’s larger owner, operator and developer of logistics retail estate, with unparalleled scale. It controls over 1.2bn square feet of property across 20 countries in 4 continents across 5,500 buildings. Prologis will rent its warehouses to businesses such as GXO Logistics. GXO will then operate the warehouse on behalf of its customer. Think of GXO as a leading systems integrator, or largest pure-play contract logistics provider, within the warehouse and logistics space, providing its customers with high-value-add services. For both these businesses (and their smaller rivals too), the future certainly looks bright.

18 June 2024

The above does not constitute investment advice and is the sole opinion of the author at the time of publication. Heptagon Capital is an investor in GXO Logistics and Prologis. The author of this piece has no personal direct investment in the business. Past performance is no guide to future performance and the value of investments and income from them can fall as well as rise.

Alex Gunz, Fund Manager, Heptagon Capital

Disclaimers

The document is provided for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or any recommendation to buy, or sell or otherwise transact in any investments. The document is not intended to be construed as investment research. The contents of this document are based upon sources of information which Heptagon Capital LLP believes to be reliable. However, except to the extent required by applicable law or regulations, no guarantee, warranty or representation (express or implied) is given as to the accuracy or completeness of this document or its contents and, Heptagon Capital LLP, its affiliate companies and its members, officers, employees, agents and advisors do not accept any liability or responsibility in respect of the information or any views expressed herein. Opinions expressed whether in general or in both on the performance of individual investments and in a wider economic context represent the views of the contributor at the time of preparation. Where this document provides forward-looking statements which are based on relevant reports, current opinions, expectations and projections, actual results could differ materially from those anticipated in such statements. All opinions and estimates included in the document are subject to change without notice and Heptagon Capital LLP is under no obligation to update or revise information contained in the document. Furthermore, Heptagon Capital LLP disclaims any liability for any loss, damage, costs or expenses (including direct, indirect, special and consequential) howsoever arising which any person may suffer or incur as a result of viewing or utilising any information included in this document.

The document is protected by copyright. The use of any trademarks and logos displayed in the document without Heptagon Capital LLP’s prior written consent is strictly prohibited. Information in the document must not be published or redistributed without Heptagon Capital LLP’s prior written consent.

Heptagon Capital LLP, 63 Brook

Street, Mayfair, London W1K 4HS

tel +44 20 7070

1800

email london@heptagon-capital.com

Partnership No: OC307355 Registered in England and Wales Authorised & Regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority

Heptagon Capital Limited is licenced to conduct investment services by the Malta Financial Services Authority.

Receive the updates

Sign up to our monthly email newsletter for the latest fund updates, webcasts and insights.

.jpg)